In 1993, Intel released the high-performance Pentium processor, the start of the long-running Pentium line.

The Pentium had many improvements over the previous processor, the Intel 486, including a faster floating-point division algorithm.

A year later, Professor Nicely, a number theory professor,

was researching reciprocals of twin prime numbers when he noticed a problem:

his Pentium sometimes generated the wrong result when performing floating-point division.

Intel considered this “an extremely minor technical problem”, but much to Intel’s surprise,

the bug became a large media story.

After weeks of criticism, mockery, and bad publicity, Intel agreed to replace everyone’s faulty Pentium chips, costing the company $475 million.

In this article, I discuss the Pentium’s division algorithm, show exactly where the bug is on the Pentium chip, take a close look at the circuitry, and explain what went wrong.

In brief, the division algorithm uses a lookup table. In 1994, Intel stated that the cause of the bug was

that five entries were omitted from the

table due to an error in a script. However, my analysis shows that 16 entries were omitted due to a

mathematical mistake in the definition of the lookup table. Five of the missing entries trigger the bug—

also called the FDIV bug after the floating-point division instruction “FDIV”—while 11 of the missing entries have no effect.

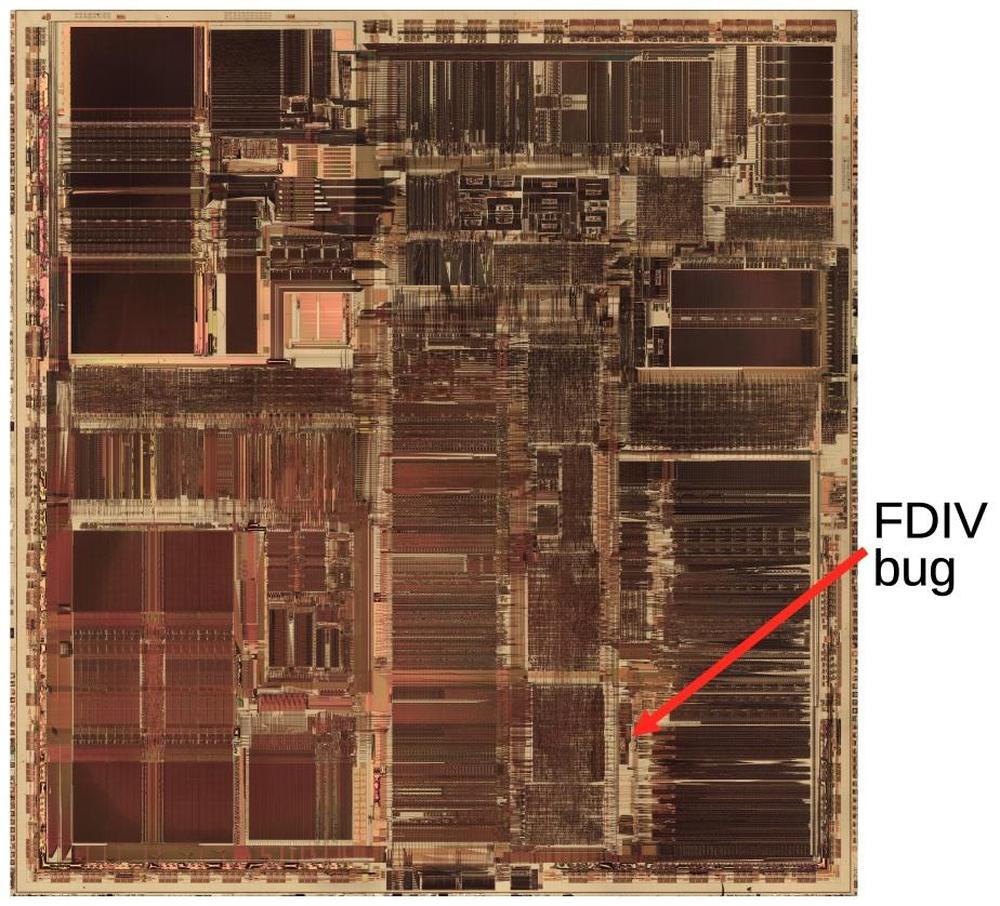

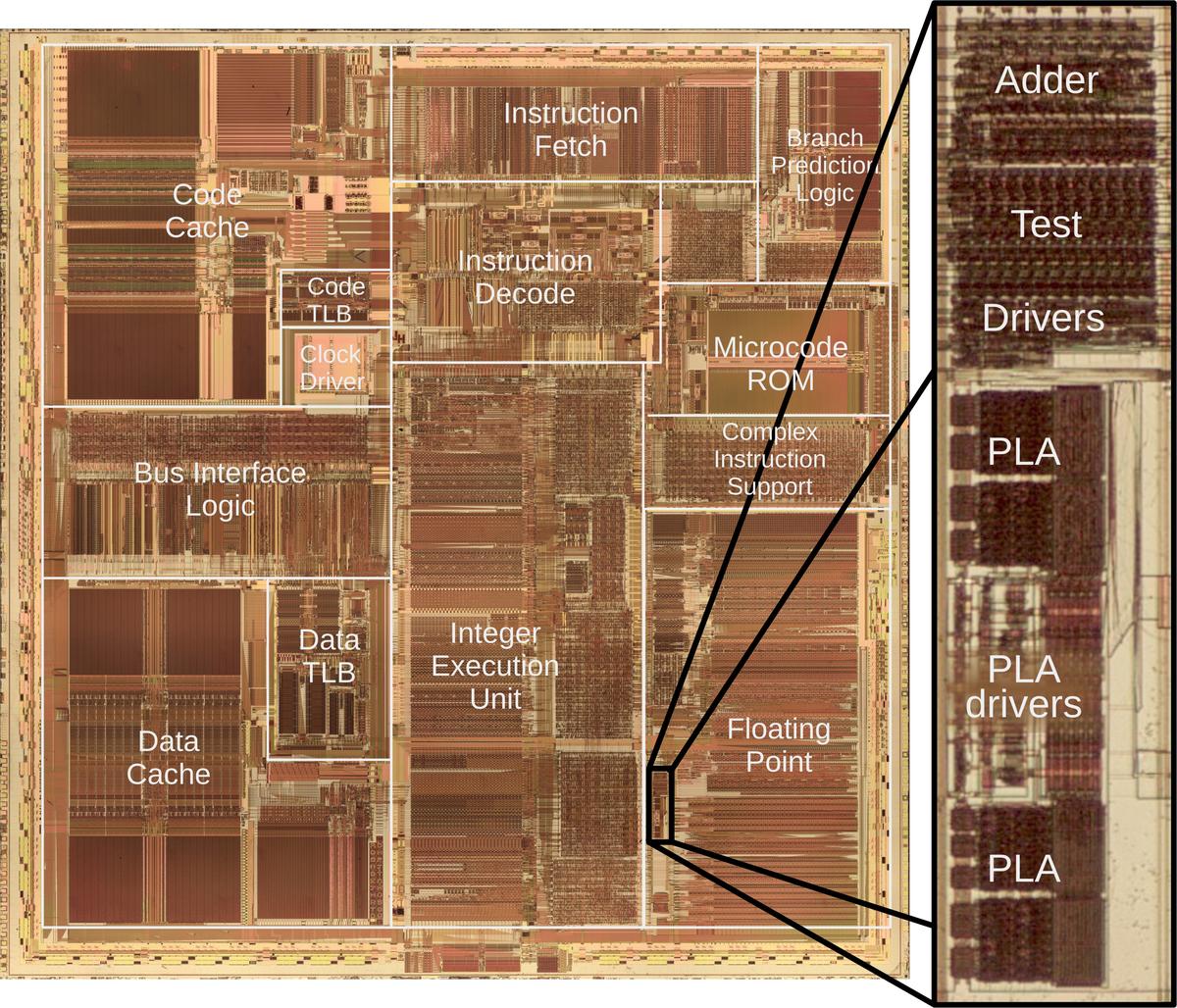

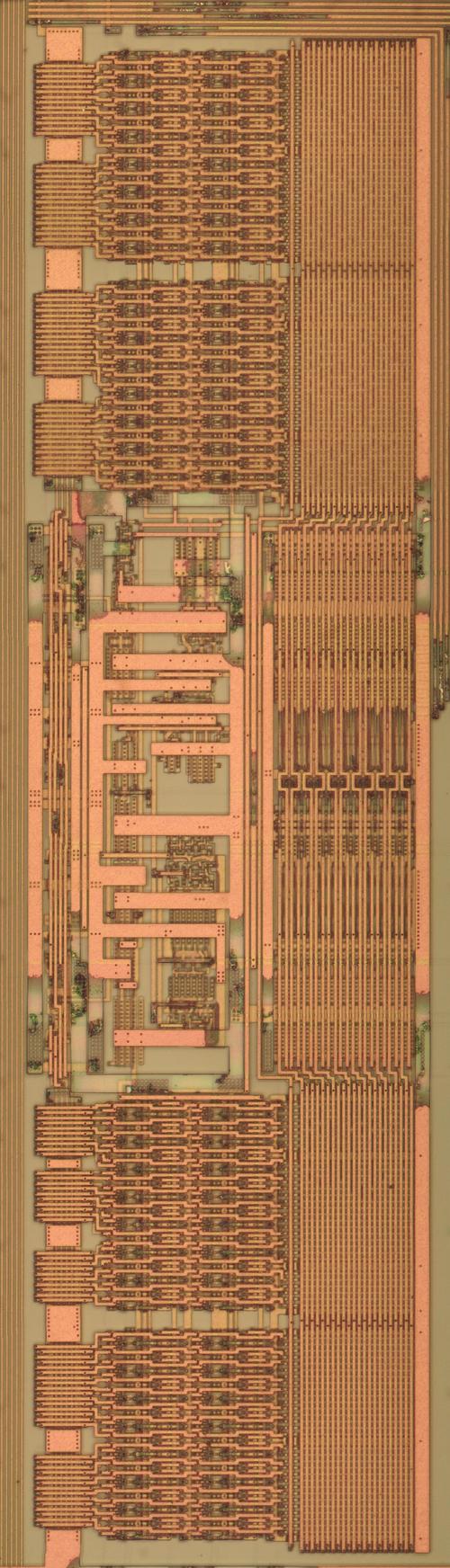

This die photo of the Pentium shows the location of the FDIV bug. Click this image (or any other) for a larger version.

Although Professor Nicely brought attention to the FDIV bug, he wasn’t the first to find it.

In May 1994, Intel’s internal testing of the Pentium revealed that

very rarely, floating-point division was slightly inaccurate.1

Since only one in 9 billion values caused the problem, Intel’s view was that the problem was trivial: “This doesn’t even qualify as an errata.” Nonetheless, Intel quietly revised the Pentium circuitry to fix the problem.

A few months later, in October, Nicely noticed erroneous results in his prime number computations.2

He soon determined that 1/824633702441 was wrong on three different Pentium computers, but his older computers gave the right answer.

He called Intel tech support but was brushed off, so

Nicely emailed a dozen computer magazines and individuals about the bug.

One of the recipients was Andrew Schulman, author of “Undocumented DOS”. He forwarded the email to Richard Smith, cofounder of a DOS software tools company.

Smith posted the email on a Compuserve forum, a 1990s version of social media.

A reporter for the journal Electronic Engineering Times spotted the Compuserve post and wrote about the Pentium bug in the November 7 issue: Intel fixes a Pentium FPU glitch.

In the article, Intel explained that the bug was in a component of the chip called a PLA (Programmable Logic Array)

that acted as a lookup table for the division operation.

Intel had fixed the bug in the latest Pentiums and

would replace faulty processors for concerned customers.3

The problem might have quietly ended here, except that Intel decided to restrict which customers could get a replacement.

If a customer couldn’t convince an Intel engineer that they needed the accuracy, they couldn’t get a fixed Pentium.

Users were irate to be stuck with faulty chips so they took their complaints to online groups such as comp.sys.intel.

The controversy spilled over into the offline world on November 22 when CNN reported on the bug.

Public awareness of the Pentium bug took off as newspapers wrote about the bug and

Intel became a punchline on talk shows.4

The situation became intolerable for Intel on December 12 when IBM announced that it was stopping shipments of Pentium computers.5

On December 19, less than two months after Nicely first reported the bug, Intel gave in and announced that it would replace the flawed chips for all customers.6

This recall cost Intel $475 million (over a billion dollars in current dollars).

Meanwhile, engineers and mathematicians were analyzing the bug, including

Tim Coe, an engineer who had designed floating-point units.7

Remarkably, by studying the Pentium’s bad divisions, Coe reverse-engineered the Pentium’s division algorithm and determined why it went wrong.

Coe and others wrote papers describing the mathematics behind the Pentium bug.8

But until now, nobody has shown how the bug is implemented in the physical chip itself.

A quick explanation of floating point numbers

At this point, I’ll review a few important things about floating point numbers.

A binary number can have a fractional part, similar to a decimal number.

For instance, the binary number 11.1001 has four digits after the binary point.

(The binary point “.” is similar to the decimal point, but for a binary number.) The first digit after the binary point represents 1/2, the second represents 1/4, and so forth.

Thus, 11.1001 corresponds to 3 + 1/2 + 1/16 = 3.5625.

A “fixed point” number such as this can express a fractional value, but its range is limited.

Floating point numbers, on the other hand, include very large numbers such as 6.02×1023 and very small numbers such as 1.055×10−34.

In decimal, 6.02×1023 has a significand (or mantissa) of 6.02, multiplied by a power of 10 with an exponent of 23.

In binary, a floating point number is represented similarly, with a significand and exponent, except the significand is multiplied by a power of 2 rather than 10.

Computers have used floating point since the early days of computing, especially for scientific computing.

For many years, different computers used incompatible formats for floating point numbers.

Eventually, a standard arose when

Intel developed the 8087 floating point coprocessor chip for use with the 8086/8088 processor.

The characteristics of this chip became a standard (IEEE 754) in 1985.9

Subsequently, most computers, including the Pentium, implemented floating point numbers according to this standard.

The result of a basic arithmetic operation is supposed to be accurate up to the last bit of the significand.

Unfortunately, division on the Pentium was occasionally much, much worse.

How SRT division works

How does a computer perform division? The straightforward way is similar to grade-school long division, except in binary.

That approach was used in the Intel 486 and earlier processors, but the process is slow, taking one clock cycle for each bit of the quotient.

The Pentium uses a different approach called SRT, performing division in base four.

Thus, SRT generates two bits of the quotient per step, rather than one, so division is twice as fast.

I’ll explain SRT in a hand-waving manner with a base-10 example; rigorous explanations are available elsewhere.10

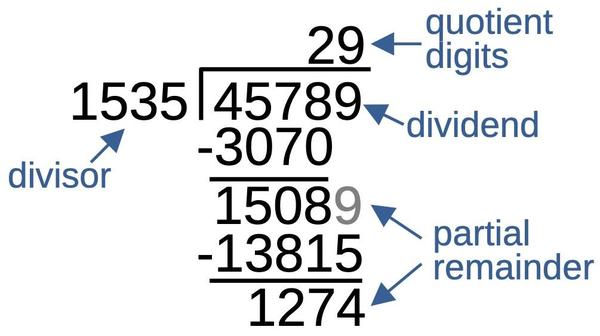

The diagram below shows base-10 long division, with the important parts named.

The dividend is divided by the divisor, yielding the quotient.

In each step of the long division algorithm, you generate one more digit of the quotient.

Then you multiply the divisor (1535) by the quotient digit (2) and subtract this from the dividend,

leaving a partial remainder.

You multiply the partial remainder by 10 and then repeat the process, generating a quotient digit and partial remainder at each step.

The diagram below stops after two quotient digits, but you can keep going to get as much accuracy as desired.

Base-10 division, naming the important parts.

Note that division is more difficult than multiplication since there is no easy way to determine each quotient digit.

You have to estimate a quotient digit, multiply it by the divisor, and then check if the quotient digit is correct.

For example, you have to check carefully to see if 1535 goes into 4578 two times or three times.

The SRT algorithm makes it easier to select the quotient digit through an unusual approach: it allows negative digits in the quotient.

With this change, the quotient digit does not need to be exact.

If you pick a quotient digit that is a bit too large, you can use a negative number for the next digit:

this will counteract the too-large digit since the next divisor will be added rather than subtracted.

The example below shows how this works.

Suppose you picked 3 instead of 2 as the first quotient digit.

Since 3 is too big, the partial remainder is negative (-261).

In normal division, you’d need to try again with a different quotient digit.

But with SRT, you keep going, using a negative digit (-1) for the quotient digit in the next step.

At the end, the quotient with positive and negative digits can be converted to the standard form: 3×10-1 = 29, the same quotient as before.

Base-10 division, using a negative quotient digit. The result is the same as the previous example.

One nice thing about the SRT algorithm is that since the quotient digit only needs to be close, a lookup table can be used to select the quotient digit.

Specifically, the partial remainder and divisor can be truncated to a few digits, making the lookup table a practical size.

In this example, you could truncate 1535 and 4578 to 15 and 45, the table says that 15 goes into 45 three times, and you can use 3 as your quotient digit.

Instead of base 10, the Pentium uses the SRT algorithm in base 4: groups of two bits.

As a result, division on the Pentium is twice as fast as standard binary division.

With base-4 SRT, each quotient digit can be -2, -1, 0, 1, or 2.

Multiplying by any of these values is very easy in hardware since multiplying by 2 can be done by a bit shift.

Base-4 SRT does not require quotient digits of -3 or 3;

this is convenient since multiplying by 3 is somewhat difficult.

To summarize, base-4 SRT is twice as fast as regular binary division, but it requires more hardware:

a lookup table, circuitry to add or subtract multiples of 1 or 2, and circuitry to convert the

quotient to the standard form.

Structure of the Pentium’s lookup table

The purpose of the SRT lookup table is to provide the quotient digit.

That is, the table takes the partial remainder p and the divisor d as inputs and

provides an appropriate quotient digit.

The Pentium’s lookup table is the cause of the division bug, as was explained in 1994.

The table was missing five entries; if the SRT algorithm accesses one of these missing entries, it generates an incorrect result.

In this section, I’ll discuss the structure of the lookup table and explain what went wrong.

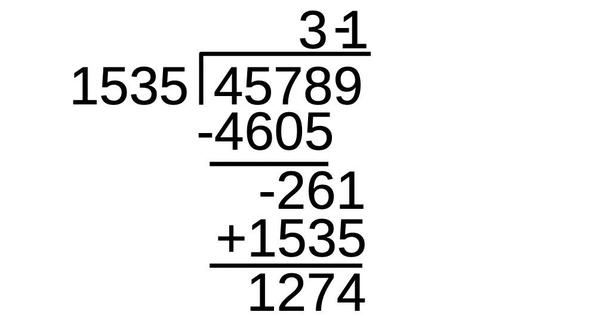

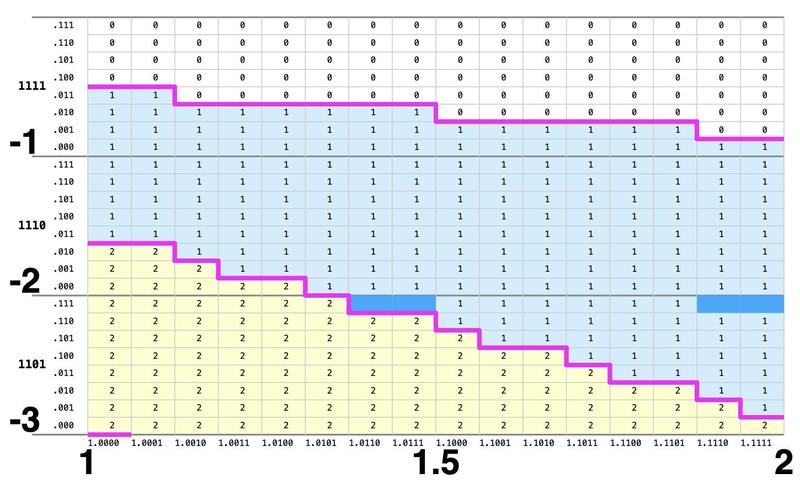

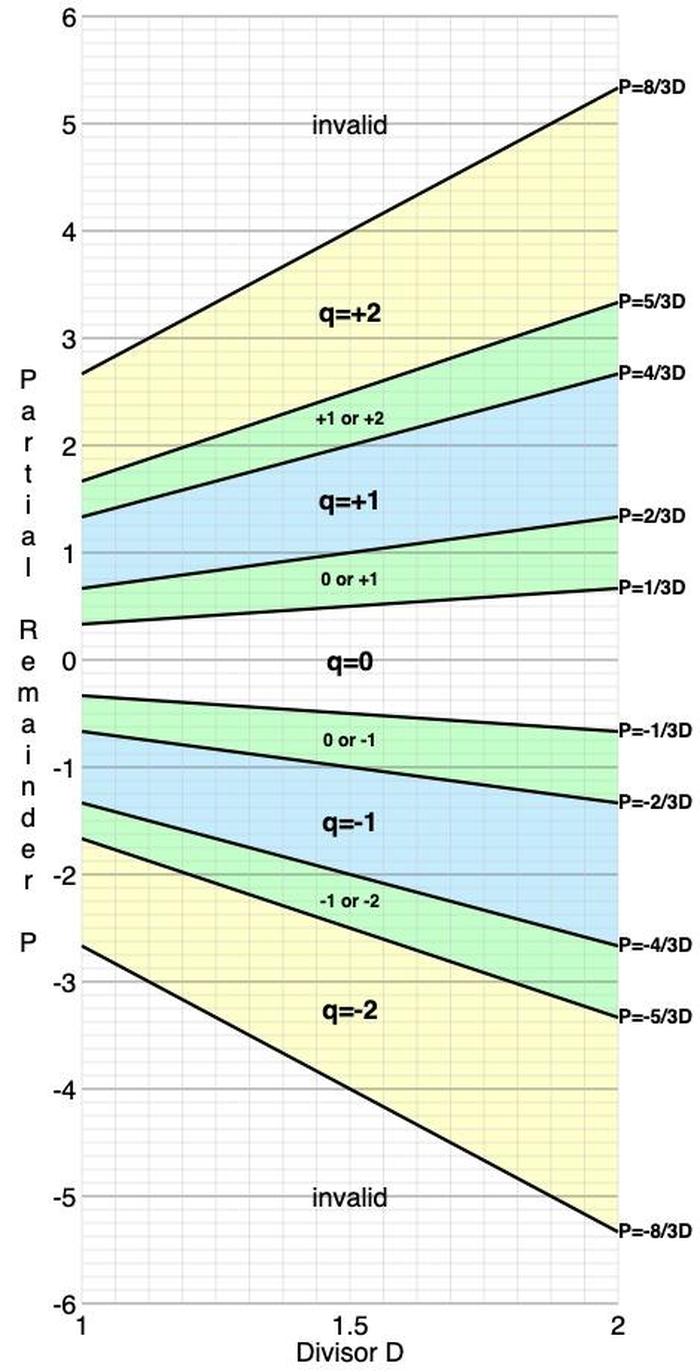

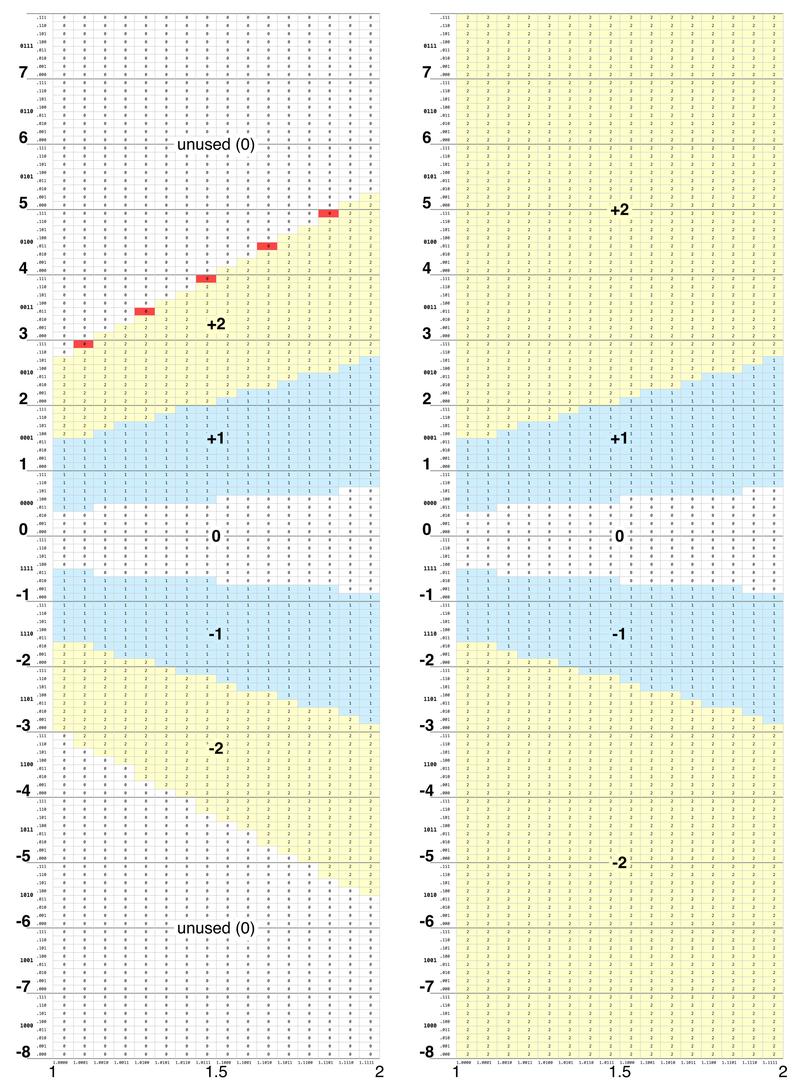

The Pentium’s lookup table contains 2048 entries, as shown below.

The table has five regions corresponding to the quotient digits +2, +1, 0, -1, and -2.

Moreover, the upper and lower regions of the table are unused (due to the mathematics of SRT).

The unused entries were filled with 0, which turns out to be very important.

In particular, the five red entries need to contain +2 but were erroneously filled with 0.

The 2048-entry lookup table used in the Pentium for division. The divisor is along the X-axis, from 1 to 2. The partial remainder is along the Y-axis, from -8 to 8. Click for a larger version.

When the SRT algorithm uses the table, the partial remainder p and the divisor d are inputs.

The divisor (scaled to fall between 1 and 2) provides the X coordinate into the table, while the partial remainder

(between -8 and 8) provides the Y coordinate.

The details of the table coordinates will be important, so I’ll go into some detail.

To select a cell, the divisor (X-axis) is truncated to a 5-bit binary value 1.dddd.

(Since the first digit of the divisor is always 1, it is ignored for the table lookup.)

The partial remainder (Y-axis) is truncated to a 7-bit signed binary value pppp.ppp.

The 11 bits indexing into the table result in a table with 211 (2048) entries.

The partial remainder is expressed in 2’s complement, so values 0000.000 to 0111.111 are non-negative values from 0 to (almost) 8, while values 1000.000 to 1111.111 are negative values from -8 to (almost) 0.

(To see the binary coordinates for the table, click on the image and zoom in.)

The lookup table is implemented in a Programmable Logic Array (PLA)

In this section, I’ll explain how the lookup table is implemented in hardware in the Pentium.

The lookup table has 2048 entries so it could be stored in a ROM with 2048 two-bit outputs.11

(The sign is not explicitly stored in the table because

the quotient digit sign is the same as the partial remainder sign.)

However, because the table is highly structured (and largely empty), the table can be stored more compactly in a structure called a Programmable Logic Array (PLA).12

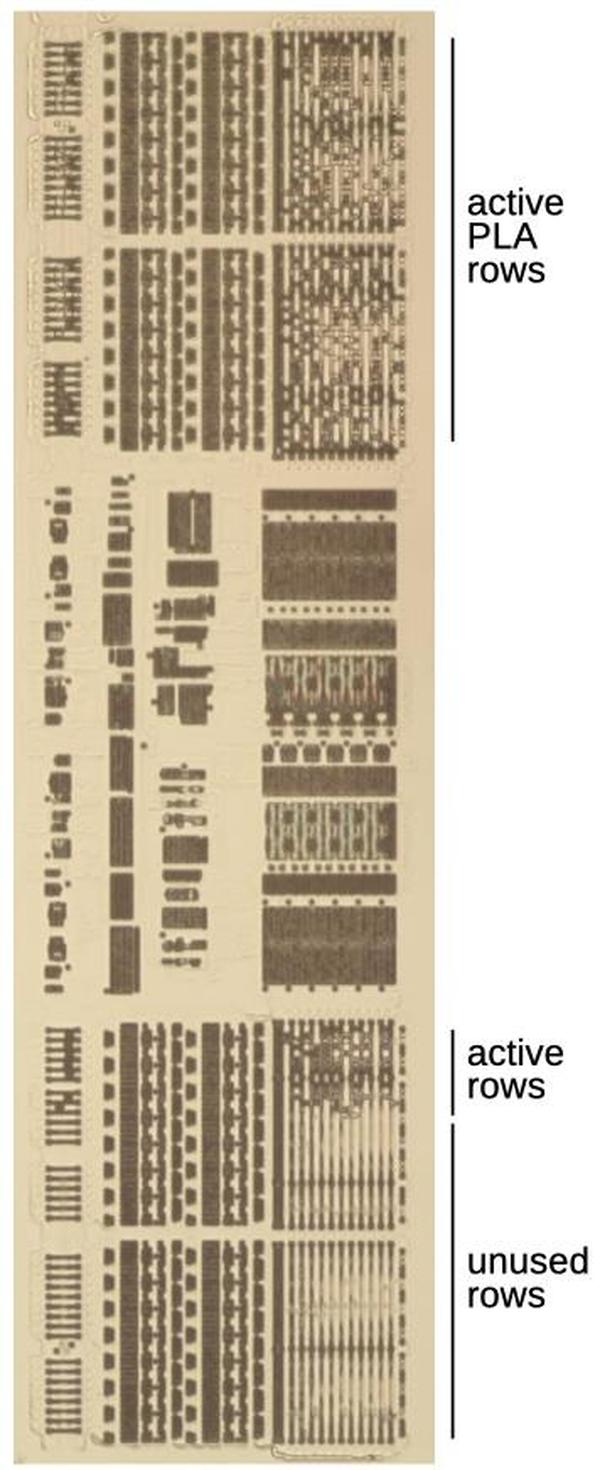

By using a PLA, the Pentium stored the table in just 112 rows rather than 2048 rows, saving an enormous amount of space.

Even so, the PLA is large enough on the chip that it is visible to the naked eye, if you squint a bit.

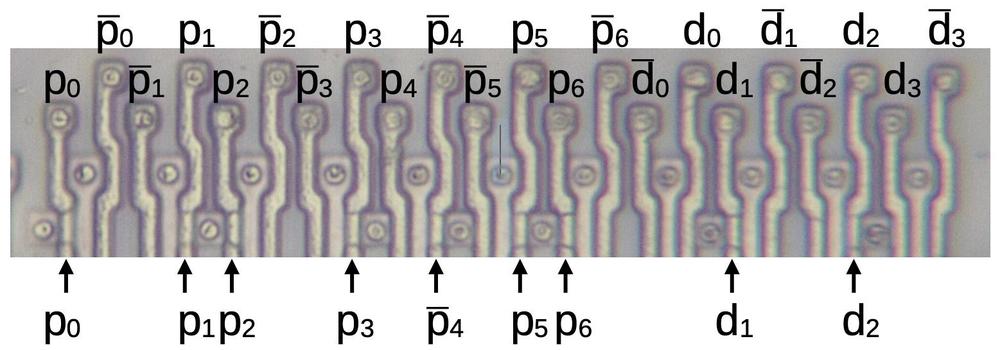

Zooming in on the PLA and associated circuitry on the Pentium die.

The idea of a PLA is to provide a dense and flexible way of implementing arbitrary logic functions.

Any Boolean logic function can be expressed as a “sum-of-products”, a collection of AND terms (products) that are OR’d together (summed).

A PLA has a block of circuitry called the AND plane that generates the desired sum terms.

The outputs of the AND plane are fed into a second block, the OR plane, which ORs the terms together.

The AND plane and the OR plane are organized as grids. Each gridpoint can either have a transistor

or not, defining the logic functions.

The point is that by putting the appropriate pattern of transistors in the grids, you can create any function.

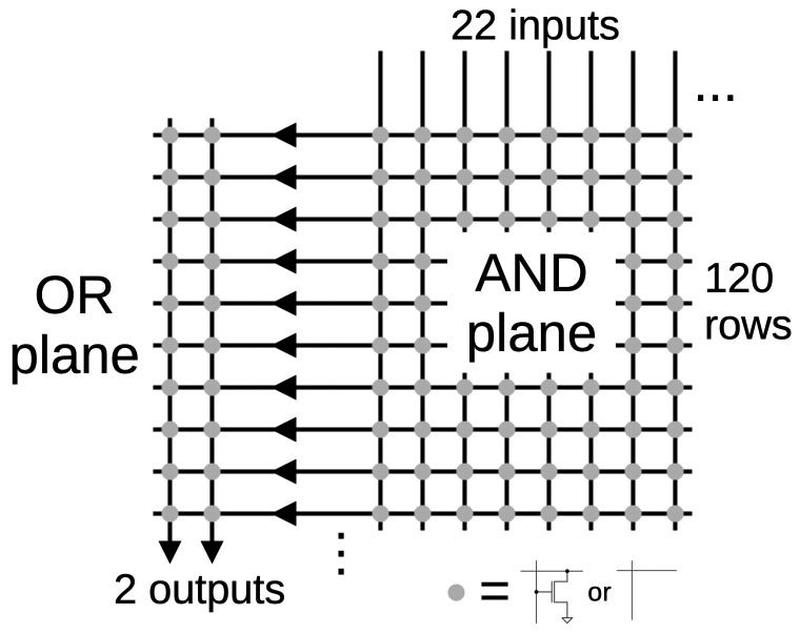

For the division PLA, there are has 22 inputs (the 11 bits from the divisor and partial remainder indices, along with their complements) and two outputs, as shown below.13

A simplified diagram of the division PLA.

A PLA is more compact than a ROM if the structure of the function allows it to be expressed with a small number of terms.14

One difficulty with a PLA is figuring out how to express the function with the minimum number of terms to

make the PLA as small as possible.

It turns out that this problem is NP-complete in general.

Intel used a program called Espresso to generate compact PLAs using heuristics.15

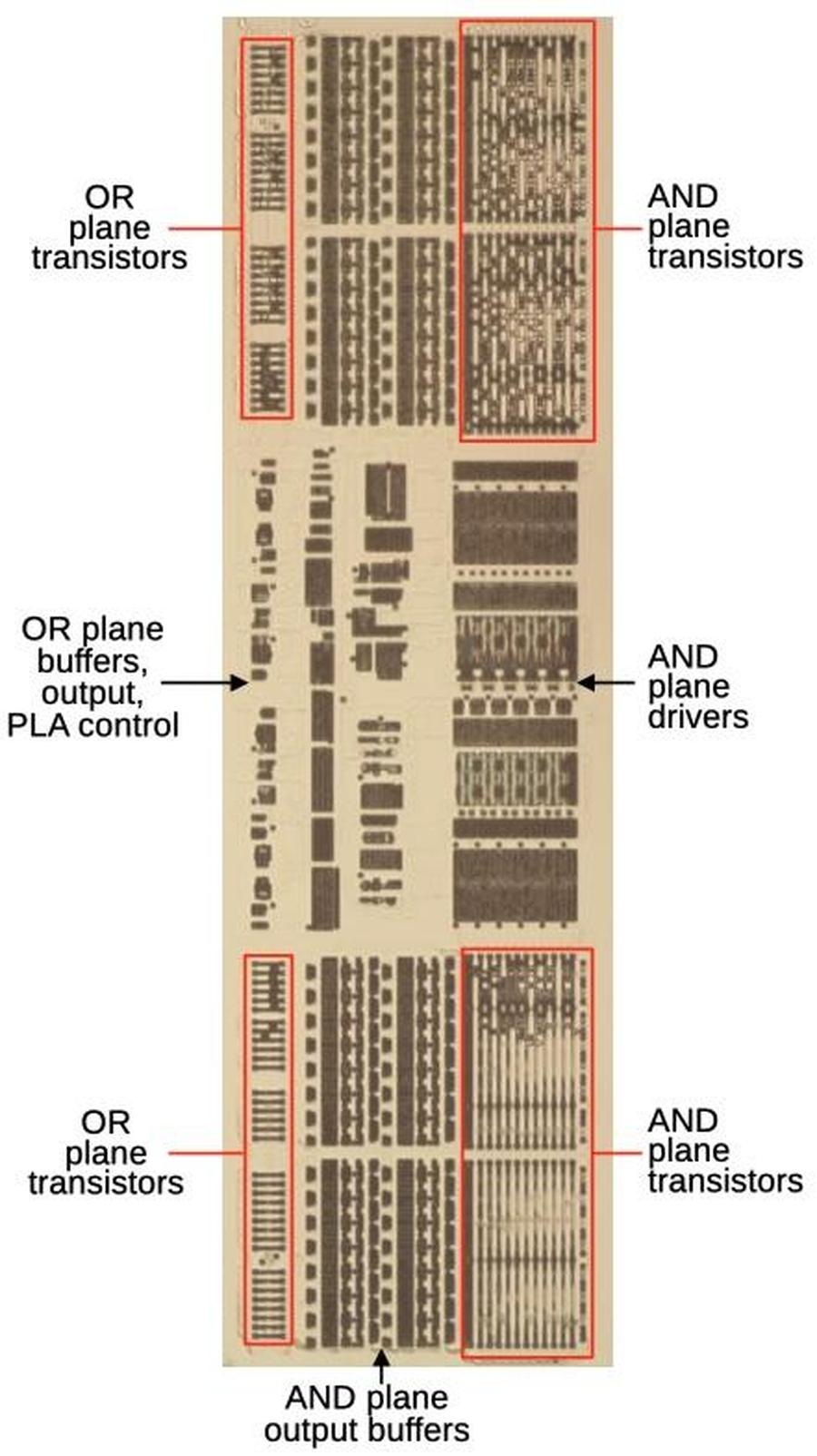

The diagram below shows the division PLA in the Pentium. The PLA has 120 rows, split into two 60-row parts with support circuitry in the middle.16

The 11 table input bits go into the AND plane drivers in the middle, which produce the 22 inputs to the PLA (each table input and its complement).

The outputs from the AND plane transistors go through output buffers and are fed into the OR plane.

The outputs from the OR plane go through additional buffers and logic in the center, producing two

output bits, indicating a ±1 or ±2 quotient.

The image below shows the updated PLA that fixes the bug; the faulty PLA looks similar except the transistor

pattern is different. In particular, the updated PLA has 46 unused rows at the bottom while the original, faulty

PLA has 8 unused rows.

The division PLA with the metal layers removed to show the silicon. This image shows the PLA in the updated Pentium, since that photo came out better.

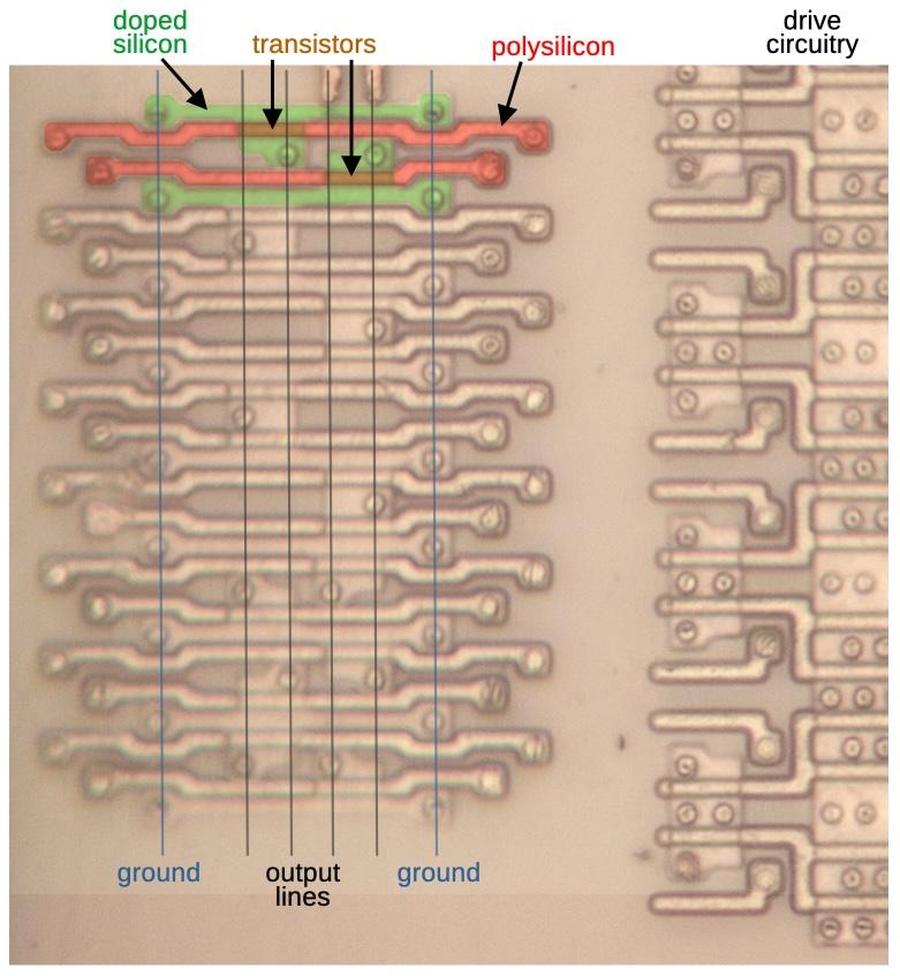

The image below shows part of the AND plane of the PLA.

At each point in the grid, a transistor can be present or absent.

The pattern of transistors in a row determines the logic term for that row.

The vertical doped silicon lines (green) are connected to ground. The vertical polysilicon lines (red) are

driven with the input bit pattern. If a polysilicon line crosses doped silicon, it forms a

transistor (orange) that will pull that row to ground when activated.17

A metal line connects all the transistor rows in a row to produce the output;

most of the metal has been removed, but some metal lines are visible at the right.

![]()

Part of the AND plane in the fixed Pentium. I colored the first silicon and polysilicon lines green and red respectively.

By carefully examining the PLA under a microscope, I extracted the pattern of transistors in

the PLA grid. (This was somewhat tedious.) From the transistor pattern, I could

determine the equations for each PLA row, and then generate the contents of the lookup table.

Note that the transistors in the PLA don’t directly map to the table contents (unlike a ROM).

Thus, there is no specific place for transistors corresponding to the 5 missing table entries.

The left-hand side of the PLA implements the OR planes (below).

The OR plane determines if the row output produces a quotient of 1 or 2.

The OR plane is oriented 90° relative to the AND plane: the inputs are horizontal polysilicon

lines (red) while the output lines are vertical.

As before, a transistor (orange) is formed where polysilicon crosses doped silicon.

Curiously, each OR plane has four outputs, even though the PLA itself has two outputs.18

Part of the OR plane of the division PLA. I removed the metal layers to show the underlying silicon and polysilicon. I drew lines for ground and outputs, showing where the metal lines were.

Next, I’ll show exactly how the AND plane produces a term.

For the division table, the inputs are the 7 partial remainder bits and 4 divisor bits, as explained

earlier.

I’ll call the partial remainder bits p6p5p4p3.p2p1p0 and the divisor bits 1.d3d2d1d0.

These 11 bits and their complements are fed vertically into the PLA as shown at the top of the diagram below.

These lines are polysilicon, so they will form transistor gates, turning on the corresponding transistor when activated.

The arrows at the bottom point to nine transistors in the first row.

(It’s tricky to tell if the polysilicon line passes next to doped silicon or over the silicon, so

the transistors aren’t always obvious.)

Looking at the transistors and their inputs shows that the first term in the PLA is generated by

p0p1p2p3p4‘p5p6d1d2.

The first row of the division PLA in a faulty Pentium.

The diagram below is a closeup of the lookup table, showing how this PLA row assigns the value 1 to four table cells (dark blue).

You can think of each term of the PLA as pattern-matching to a binary pattern that can include “don’t care” values.

The first PLA term (above) matches the pattern P=110.1111, D=x11x, where the “don’t care” x values can be either 0 or 1.

Since one PLA row can implement multiple table cells, the PLA is more efficient than a ROM;

the PLA uses 112 rows, while a ROM would require 2048 rows.

The first entry in the PLA assigns the value 1 to the four dark blue cells.

Geometrically, you can think of each PLA term (row) as covering a rectangle or rectangles in the table.

However, the rectangle can’t be arbitrary, but must be aligned on a bit boundary.

Note that each “bump” in the table boundary (magenta) requires a separate rectangle and thus a separate PLA row.

(This will be important later.)

One PLA row can generate a large rectangle, filling in many table cells at once,

if the region happens to be aligned nicely.

For instance, the third term in the PLA matches d=xxxx, p=11101xx.

This single PLA row efficiently fills in

64 table cells as shown below, replacing the 64 rows that would be required in a ROM.

The third entry in the PLA assigns the value 1 to the 64 dark blue cells.

To summarize, the pattern of transistors in the PLA implements a set of equations, which define

the contents of the table, setting the quotient to 1 or 2 as appropriate.

Although the table has 2048 entries, the PLA represents the contents in just 112 rows.

By carefully examining the transistor pattern, I determined the table contents in a faulty Pentium and

a fixed Pentium.

The mathematical bounds of the lookup table

As shown earlier, the lookup table has regions corresponding to quotient digits of +2, +1, 0, -1, and -2.

These regions have irregular, slanted shapes, defined by mathematical bounds.

In this section, I’ll explain these mathematical bounds since

they are critical to understanding how the Pentium bug occurred.

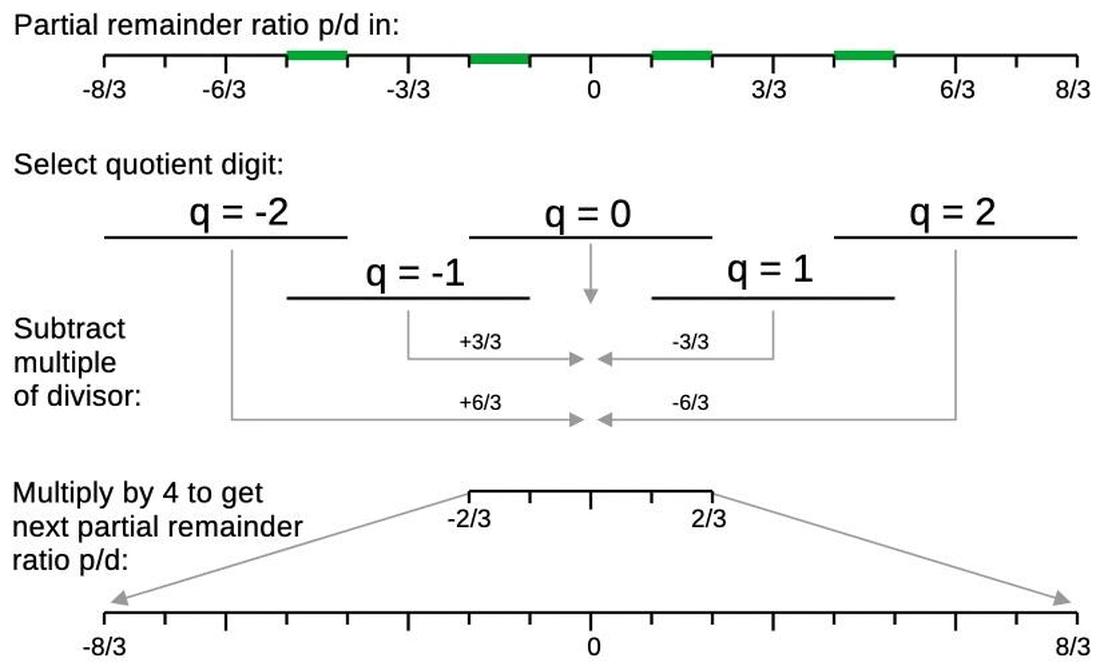

The essential step of the division algorithm is to divide

the partial remainder p by the divisor d to get the quotient digit.

The following diagram shows how p/d determines the quotient digit. The ratio p/d will define a point on

the line at the top. (The point will be in the range [-8/3, 8/3] for mathematical reasons.)

The point will fall into one of the five lines below, defining the quotient digit q. However, the five quotient

regions overlap; if p/d is in one of the green segments, there are two possible quotient digits.

The next part of the diagram illustrates how subtracting

q*d from the partial remainder p shifts p/d into the middle, between -2/3 and 2/3.

Finally, the result is multiplied by 4 (shifted left by two bits), expanding19 the interval back to [-8/3, 8/3], which is the same size as the original interval.

The 8/3 bound may seem arbitrary, but the motivation is that

it ensures tht the new interval is the same size as the original interval, so the process can be repeated.

(The bounds are all thirds for algebraic reasons; the value 3 comes from base 4 minus 1.20)

The input to a division step is processed, yielding the input to the next step.

Note that the SRT algorithm has some redundancy, but cannot handle q values that are “too wrong”.

Specifically, if p/d is in a green region,

then either of two q values can be selected.

However, the algorithm cannot recover from a bad q value in general.

The relevant case is that if q is supposed to be 2 but 0 is selected,

the next partial remainder will be outside the interval and the algorithm can’t recover.

This is what causes the FDIV bug.

The diagram below shows the structure of the SRT lookup table (also called the P-D table since the axes are p and d).

Each bound in the diagram above turns into a line in the table.

For instance, the green segment above with p/d between 4/3 and 5/3 turns into a green region in the

table below with 4/3 d ≤ p ≤ 5/3 d.

These slanted lines show the regions in which a particular quotient digit q can be used.

The P-D table specifies the quotient digit for a partial remainder (Y-axis) and divisor (X-axis).

The lookup table in the Pentium is based on the above table, quantized with a q value in each cell.

However, there is one more constraint to discuss.

Carry-save and carry-lookahead adders

The Pentium’s division circuitry uses a special circuit to perform addition and subtraction efficiently:

the carry-save adder.

One consequence of this adder is that each access to the lookup table may go to the cell just below

the “right” cell. This is expected and should be fine, but in very rare and complicated circumstances,

this behavior causes an access to one of the Pentium’s five missing cells, triggering the division bug.

In this section, I’ll discuss why the division circuitry uses a carry-save adder, how the carry-save adder works,

and how the carry-save adder triggers the FDIV bug.

The problem with addition is that carries make addition slow.

Consider calculating 99999+1 by hand.

You’ll start with 9+1=10, then carry the one, generating another carry, which generates another carry, and so forth, until you go through all the digits.

Computer addition has the same problem.

If you’re adding, say, two 64-bit numbers, the low-order bits can generate a carry that then propagates through all 64 bits.

The time for the carry signal to go through 64 layers of circuitry is significant and can limit CPU performance.

As a result, CPUs use special circuits to make addition faster.

The Pentium’s division circuitry uses an unusual adder circuit called a carry-save adder to add (or subtract) the divisor and the partial remainder.

A carry-save adder speeds up addition if you are performing a bunch of additions, as happens during division.

The idea is that instead of adding a carry to each digit as it happens, you hold onto the carries in a separate word.

As a decimal example, 499+222 would be 611 with carries 011; you don’t carry the one to the second digit, but hold onto it.

The next time you do an addition, you add in the carries you saved previously, and again save any new carries.

The advantage of the carry-save adder is that the sum and carry at each digit position can be computed in parallel, which is fast.

The disadvantage is that you need to do a slow addition at the end of the sequence of additions to add in the remaining carries to get the final answer.

But if you’re performing multiple additions (as for division), the carry-save adder is faster overall.

The carry-save adder creates a problem for the lookup table.

We need to use the partial remainder as an index into the lookup table.

But the carry-save adder splits the partial remainder into two parts: the sum bits and the carry bits.

To get the table index, we need to add the sum bits and carry bits together.

Since this addition needs to happen for every step of the division, it seems like we’re back to using a slow adder and the carry-save adder has just made things worse.

The trick is that we only need 7 bits of the partial remainder for the table index, so we can use

a different type of adder—a carry-lookahead adder—that calculates each carry in parallel using brute force logic.

The logic in a carry-lookahead adder gets more and more complex for each bit so a carry-lookahead adder is impractical for large words, but it is practical for a 7-bit value.

The photo below shows the carry-lookahead adder used by the divider.

Curiously, the adder is an 8-bit adder but only 7 bits are used;

perhaps the 8-bit adder was a standard logic block at Intel.21

I’ll just give a quick summary of the adder here, and leave the details for another post.

At the top, logic gates compute signals in parallel for each of the 8 pairs of inputs: sum, carry generate, and carry propagate.

Next, the complex carry-lookahead logic determines in parallel if there will be a carry at each position.

Finally, XOR gates apply the carry to each bit.

The circuitry in the middle is used for testing; see the footnote.22

At the bottom, the drivers amplify control signals for various parts of the adder and send the PLA output to other parts of the chip.23

By counting the blocks of repeated circuitry, you can see which blocks are 8 bits wide, 11, bits wide, and so forth.

The carry-lookahead logic is different for each bit, so there is no repeated structure.

![]()

The carry-lookahead adder that feeds the lookup table. This block of circuitry is just above the PLA on the die. I removed the metal layers, so this photo shows the doped silicon (dark) and the polysilicon (faint gray).

The carry-save and carry-lookahead adders may seem like implementation trivia, but they are

a critical part of the FDIV bug because they change the constraints on the table.

The cause is that the partial remainder is 64 bits,24 but the adder that computes the table

index is 7 bits.

Since the rest of the bits are truncated before the sum, the partial remainder sum for the table index

can be slightly lower than the real partial remainder.

Specifically, the table index can be one cell lower than the correct cell, an offset of 1/8.

Recall the earlier diagram with diagonal lines separating the regions.

Some (but not all) of these lines must be shifted down by 1/8 to account for the carry-save effect,

but Intel made the wrong adjustment, which is the root cause of the FDIV error.

(This effect was well-known at the time and mentioned in papers on SRT division, so Intel shouldn’t have gotten it wrong.)

An interesting thing about the FDIV bug is how extremely rare it is.

With 5 bad table entries out of 2048, you’d expect erroneous divides to be very common.

However, for complicated mathematical reasons involving the carry-save adder

the missing table entries are almost never encountered:

only about 1 in 9 billion random divisions will encounter a problem.

To hit a missing table entry, you need an “unlucky” result from the carry-save adder multiple

times in a row, making the odds similar to winning the lottery, if the lottery prize were a division error.25

What went wrong in the lookup table

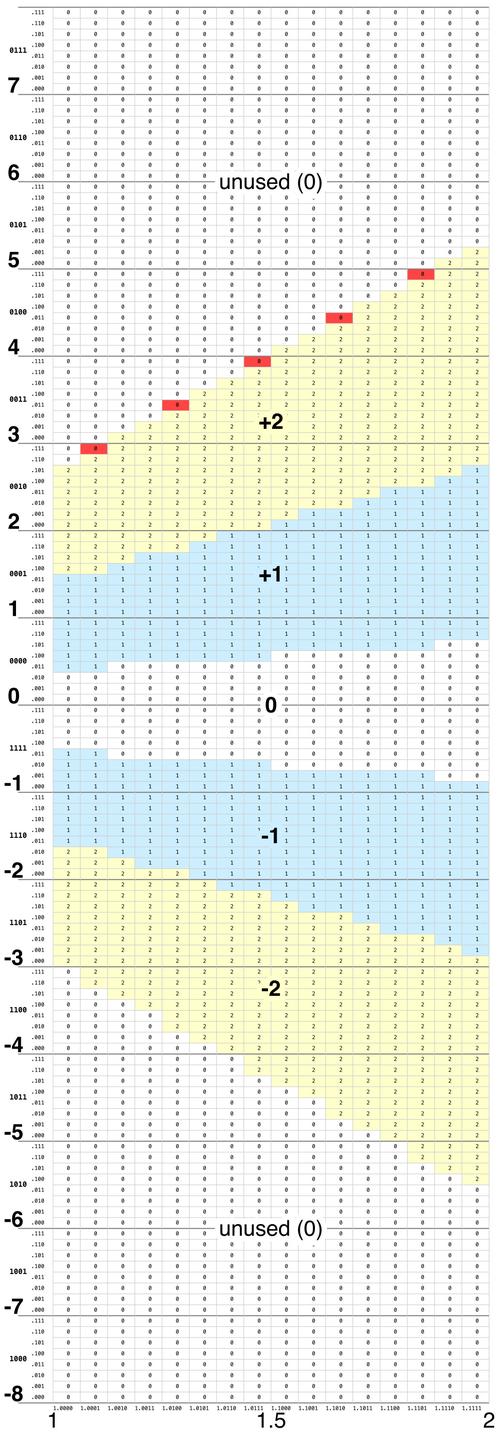

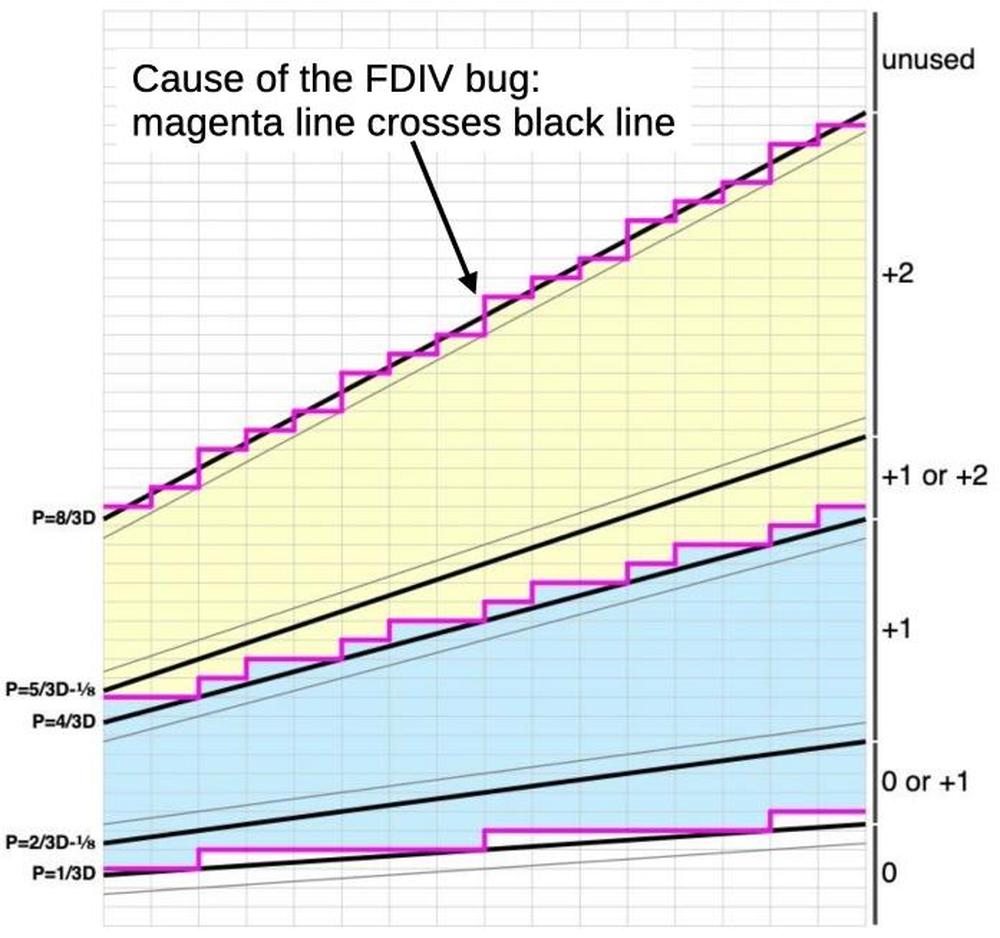

I consider the diagram below to be the “smoking gun” that explains how the FDIV bug happens:

the top magenta line should be above the sloping black line, but it crosses the black line repeatedly.

The magenta line carefully stays above the gray line, but that’s the wrong line.

In other words, Intel picked the wrong bounds line when defining the +2 region of the table.

In this section, I’ll explain why that causes the bug.

The top half of the lookup table, explaining the root of the FDIV bug.

The diagram is colored according to the quotient values stored in the Pentium’s lookup table: yellow is +2,

blue is +1, and white is 0, with magenta lines showing the boundaries between different values.

The diagonal black lines are the mathematical constraints on the table, defining the region that

must be +2, the region that can be +1 or +2, the region that must be +1, and so forth.

For the table to be correct, each cell value in the table must satisfy these constraints.

The middle magenta line is valid:

it remains between the two black lines (the redundant +1 or +2 region), so all the cells that need

to be +1 are +1 and all the cells that need to be +2 are +2, as required.

Likewise, the bottom magenta line remains between the black lines.

However, the top magenta line is faulty: it must remain above the top black line, but it crosses

the black line. The consequence is that some cells that need to be +2 end up holding 0: these are the missing

cells that caused the FDIV bug.

Note that the top magenta line stays above the diagonal gray line while following it as closely

as possible. If the gray line were the correct line, the table would be perfect.

Unfortunately, Intel picked the wrong constraint line for the table’s upper bound when the table was

generated.26

But why are some diagonal lines lowered by 1/8 and other lines are not lowered?

As explained in the previous section, as a consequence of the carry-save adder truncation,

the table lookup may end up one cell lower than the actual p value would indicate, i.e. the

p value for the table index is 1/8 lower than that actual value.

Thus, both the correct cell and the cell below must satisfy the SRT constraints.

Thus, the line moves down if that makes the constraints stricter but does not move down

if that would expand the redundant area.

In particular, the top line must not be move down, but clearly Intel moved the line down and generated the

faulty lookup table.

Intel, however, has a different explanation for the bug.

The Intel white paper states that the problem was in a script that downloaded the table into a PLA: an error caused the script to omit a few entries from the PLA.27

I don’t believe this explanation: the missing terms match a mathematical error, not a copying error.

I suspect that Intel’s statement is technically true but misleading: they ran a C program

(which they called a script) to generate the table but the program had a mathematical error

in the bounds.

In his book “The Pentium Chronicles”, Robert Colwell, architect of the Pentium Pro, provides

a different explanation of the FDIV bug.

Colwell claims that the Pentium design originally used the same lookup table as the 486,

but shortly before release, the engineers were pressured by management to shrink the circuitry to save die space.

The engineers optimized the table to make it smaller and

had a proof that the optimization would work.

Unfortunately, the proof was faulty, but the testers trusted the engineers and didn’t test the modification thoroughly, causing the Pentium to be released with the bug.

The problem with this explanation is that the Pentium was designed from the start with a completely different division algorithm from the 486: the Pentium uses radix-4 SRT, while the 486 uses standard binary division.

Since the 486 doesn’t have a lookup table, the story falls apart.

Moreover, the PLA could trivially have been made smaller by removing the 8 unused rows, so the engineers clearly weren’t trying to shrink it.

My suspicion is that since Colwell developed the Pentium Pro in Oregon but the original Pentium was developed in California, Colwell didn’t get firsthand information on the Pentium problems.

How Intel fixed the bug

Intel’s fix for the bug was straightforward but also surprising.

You’d expect that Intel added the five missing table values to the PLA, and this is what was

reported at the time.

The New York Times wrote that Intel fixed the flaw by adding several dozen transistors to the chip.

EE Times wrote that “The fix entailed adding terms, or additional gate-sequences, to the PLA.”

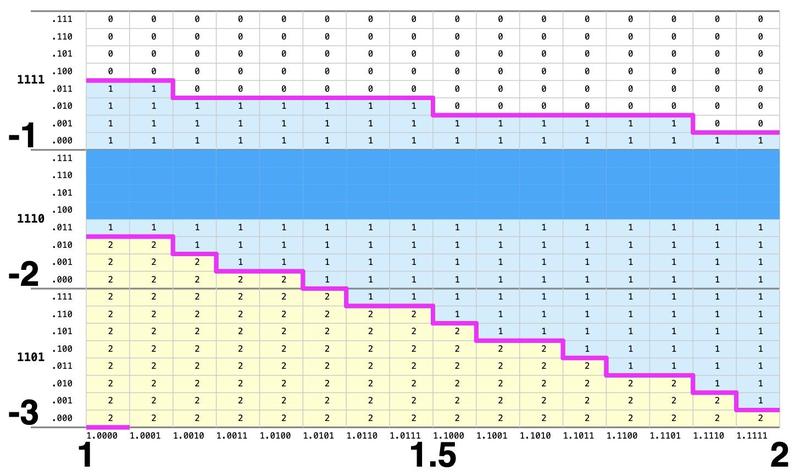

However, the updated PLA (below) shows something entirely different.

The updated PLA is exactly the same size as the original PLA. However,

about 1/3 of the terms were removed from the PLA, eliminating hundreds of transistors.

Only 74 of the PLA’s 120 rows are used, and the rest are left empty. (The original PLA had 8 empty rows.)

How could removing terms from the PLA fix the problem?

The updated PLA has 46 unused rows.

The explanation is that

Intel didn’t just fill in the five missing table entries with the correct value of 2.

Instead, Intel filled all the unused table entries with 2, as shown below.

This has two effects.

First, it eliminates any possibility of hitting a mistakenly-empty entry.

Second, it makes the PLA equations much simpler.

You might think that more entries in the table would make the PLA larger, but the number of

PLA terms depends on the structure of the data.

By filling the unused cells with 2, the jagged borders between the unused regions (white) and the “2” regions (yellow) disappear.

As explained earlier, a large rectangle can be covered by a single PLA term, but a jagged border requires

a lot of terms.

Thus, the updated PLA is about 1/3 smaller than the original, flawed PLA.

One consequence is that the terms in the new PLA are completely different from the terms in the

old PLA so one can’t point to the specific transistors that fixed the bug.

Comparison of the faulty lookup table (left) and the corrected lookup table (right).

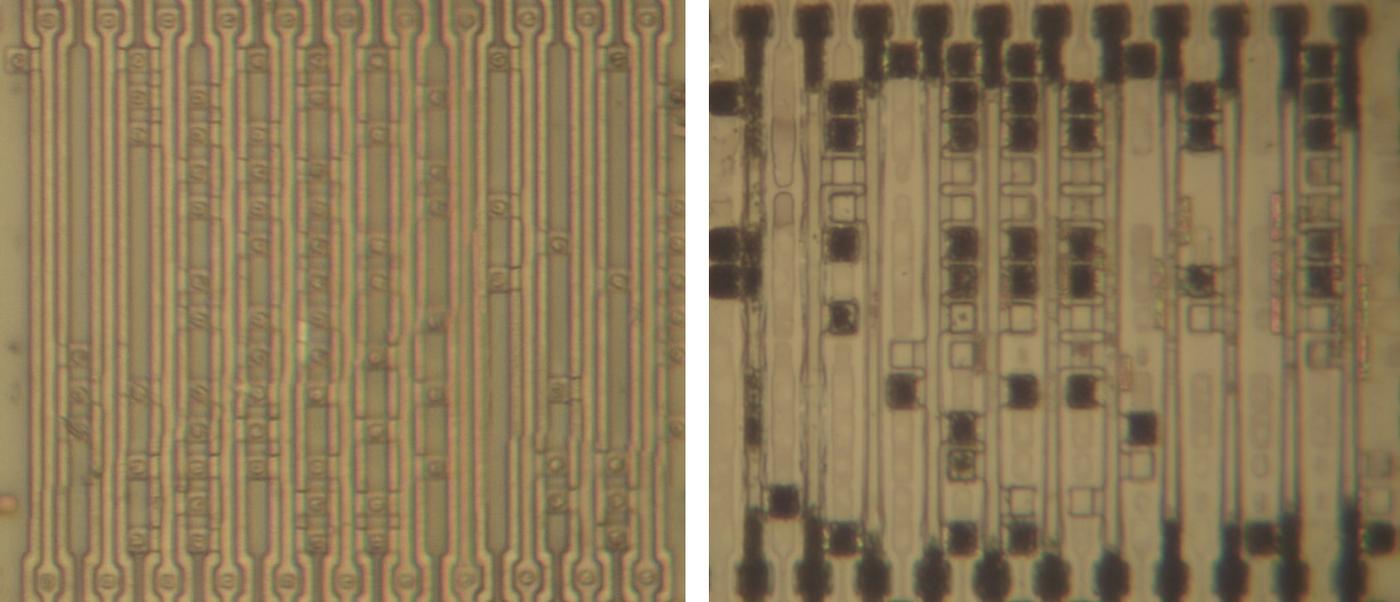

The image below shows the first 14 rows of the faulty PLA and the first 14 rows of the fixed PLA. As you can

see, the transistor pattern (and thus the PLA terms) are entirely different.

The doped silicon is darkened in the second image due to differences in how I processed the dies to remove

the metal layers.

Top of the faulty PLA (left) and the fixed PLA (right). The metal layers were removed to show the silicon of the transistors. (Click for a larger image.)

Impact of the FDIV bug

How important is the Pentium bug? This became a highly controversial topic.

A failure of a random division operation is very rare: about one in 9 billion values will trigger the bug.

Moreover, an erroneous division is still mostly accurate: the error is usually in the 9th or 10th decimal

digit, with rare worst-case error in the 4th significant digit.

Intel’s whitepaper claimed that a typical user would encounter a problem once every 27,000 years, insignificant compared to other sources of error such as DRAM bit flips.

Intel said: “Our overall conclusion is that the flaw in the floating point unit of the Pentium processor is of no concern to the vast majority of users.

A few users of applications in the scientific/engineering and financial engineering fields may need to employ either an updated processor without the flaw or a software workaround.”

However, IBM performed their own analysis,29 suggesting that the problem could hit customers every few days, and IBM suspended Pentium sales. (Coincidentally, IBM had a competing processor, the PowerPC.)

The battle made it to major newspapers; the Los Angeles Times split the difference with Study Finds Both IBM, Intel Off on Error Rate.

Intel soon gave in and agreed to replace all the Pentiums, making the issue moot.

I mostly agree with Intel’s analysis. It appears that only one person (Professor Nicely) noticed the bug

in actual use.28

The IBM analysis seems contrived to hit numbers that trigger the error.

Most people would never hit the bug and even if they hit it, a small degradation in floating-point accuracy is unlikely to matter to most people.

Looking at society as a whole, replacing the Pentiums was a huge expense for minimal gain.

On the other hand, it’s reasonable for customers to expect an accurate processor.

Note that the Pentium bug is deterministic: if you use a specific divisor and dividend that trigger the problem,

you will get the wrong answer 100% of the time.

Pentium engineer Ken Shoemaker suggested that the outcry over the bug was because it was so easy for

customers to reproduce.

It was hard for Intel to argue that customers would never encounter the bug when customers could trivially

see the bug on their own computer, even if the situation was artificial.

Conclusions

The FDIV bug is one of the most famous processor bugs.

By examining the die, it is possible to see exactly where it is on the chip.

But Intel has had other important bugs.

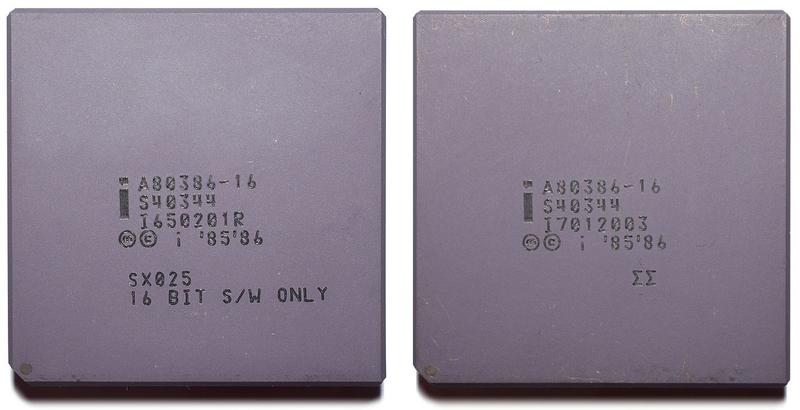

Some early 386 processors had a 32-bit multiply problem.

Unlike the deterministic FDIV bug, the 386 would unpredictably produce the wrong results under particular temperature/voltage/frequency conditions.

The underlying issue was a layout problem that didn’t provide enough elctrical margin to handle the worst-case situation.

Intel sold the faulty chips but restricted them to the 16-bit market; bad chips were labeled “16 BIT S/W ONLY”, while the good processors were marked with a double sigma.

Although Intel had to suffer through embarrassing headlines such as Some 386 Systems Won’t Run 32-Bit Software, Intel Says, the bug was soon forgotten.

Bad and good versions of the 386. Note the labels on the bottom line. Photos (L), (R) by Thomas Nguyen, (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another memorable Pentium issue was the “F00F bug”, a problem where a particular instruction sequence starting with F0 0F would cause the processor to lock up until rebooted.30

The bug was found in 1997 and solved with an operating system update.

The bug is presumably in the Pentium’s voluminous microcode. The microcode is too complex for me to analyze,

so don’t expect a detailed blog post on this subject. 🙂

You might wonder why Intel needed to release a new revision of the Pentium to fix the FDIV bug, rather than just updating the microcode.

The problem was that microcode for the Pentium (and earlier processors) was hard-coded into a ROM and couldn’t be modified.

Intel added patchable microcode to the Pentium Pro (1995), allowing limited modifications to the microcode.

Intel originally implemented this feature for chip debugging and testing.

But after the FDIV bug, Intel realized that patchable microcode was valuable for bug fixes too.31

The Pentium Pro stores microcode in ROM, but it also has a static RAM that holds up to 60 microinstructions.

During boot, the BIOS can load a microcode patch into this RAM.

In modern Intel processors, microcode patches have been used for problems ranging from the Spectre vulnerability to voltage problems.

The Pentium PLA with the top metal layer removed, revealing the M2 and M1 layers. The OR and AND planes are at the top and bottom, with drivers and control logic in the middle.

As the number of transistors in a processor increased exponentially, as described by Moore’s Law,

processors used more complex circuits and algorithms. Division is one example.

Early microprocessors such as the Intel 8080 (1974, 6000 transistors) had no hardware support for

division or floating point arithmetic. The Intel 8086 (1978, 29,000 transistors) implemented integer division

in microcode but required the 8087 coprocessor chip for floating point. The Intel 486 (1989, 1.2 million transistors) added floating-point support on the chip.

The Pentium (1993, 3.1 million transistors) moved to the

faster but more complicated SRT division algorithm.

The Pentium’s division PLA alone has roughly 4900 transistor sites, more than a MOS Technology 6502 processor—one component of the Pentium’s division circuitry uses more transistors than an entire 1975 processor.

The long-term effect of the FDIV bug on Intel is a subject of debate.

On the one hand, competitors such as AMD benefitted from Intel’s error.

AMD’s ads poked fun at the Pentium’s problems by listing features of AMD’s chips such as “You don’t have to double check your math” and “Can actually handle the rigors of complex calculations like division.”

On the other hand, Robert Colwell, architect of the Pentium Pro, said that the FDIV bug may have been a net benefit to Intel as it created enormous name recognition for the Pentium, along with a demonstration that Intel was willing to back up its brand name.

Industry writers agreed; see The Upside of the Pentium Bug.

In any case, Intel survived the FDIV bug; time will tell how Intel survives its current problems.

I plan to write more about the implementation of the Pentium’s PLA, the adder, and the test circuitry. Until then,

you may enjoy reading about the Pentium Navajo rug.

(The rug represents the P54C variant of the Pentium, so it is safe from the FDIV bug.)

Thanks to Bob Colwell and Ken Shoemaker for helpful discussions.